Throughout South Louisiana on Friday and Saturday night, buildings that are dormant all week come roaring to life. Flashing arrow signs advertise the evening’s entertainment and empty gravel or grass parking lots fill up with cars and trucks just after sundown. Couples and singles arrive, mill about outside, greeting old friends and making new ones.

The first strains of the accordion fill the air, followed quickly by the sharp snap of the snare drum. In an instant, the entire building becomes a speaker box-pulsing with the sound of the entire band, propelled (ever forward) by the syncopation of the bass player and drummer. Even in the parking lot, the urge to move is almost irresistible, encouraging those just arriving to move a little quicker to get inside for their first dance of the night.

Dancehall attendees are usually dressed one of two ways–to the nines in their finest new clothes, or in older, comfortable worn in gear that falls somewhere between workout and work clothes. The crowd sports equal parts modern urban and rural country styles–as many baseball caps as cowboy hats, oversized t-shirts as tucked-in Western snap shirts, baggy pants as starched Wranglers with huge belt buckles, and as many sneakers as cowboy boots. No matter their skin color or what they are wearing, everyone is here for the same thing–to dance. Regardless of the outside temperature, most dancers will be drenched in sweat before the night is over.

South Louisiana was once dotted with dancehalls like these—many communities were outfitted with at least one. Equal parts bar, performance hall, and community center, the traditional dancehall provided a space for much needed recreation. The majority of these legendary institutions have closed their doors, but the few that remain open are now a frequent stop for tourists from all over the world.

Day-to-day life in Louisiana has traditionally meant hard physical labor. Working the land, a machine, oil derrick, washing clothes or cooking and cleaning, enduring the seasonal highs and lows from before sun-up until after sundown six days a week didn’t leave one with much energy or money for a party. Saturday night was special: time to leave behind all your troubles, dress up in your second best clothes (you need the best for church in the morning!) and head out to the dancehall.

The whole extended family loaded up in a wagon (or in later years a car) and drove to the outskirts of town. After traveling down the dark and dirty country roads, a lighted building appeared in the distance. As the vehicle grew nearer, faint music cut the humid night air. The area around the building abuzz with activity: children running and playing a game of tag, women greeting each other, and men shaking hands and slapping each other on the back. A man with a cigar box collected a small fee at the entrance. Inside, the band, made up of local community members, set up on one end of a room, and the floor in front of the band is filled with dancers, the floorboards alive under their feet, pulsing with the dancers and slightly bowing under the weight. Around the edge of the room women, both young and old, sit and wait to be asked to dance. Young women ask their mothers if they can have a dance with their new beau–hoping he will ask. The men mill about, searching the sea of faces, knowing each one. Everyone talks about the latest community news. In one small room, infants are rocked amid the noise and bustle, their mothers bidding them to sleep so that they can enjoy a dance themselves. Men step out into the cool night air, reaching into their back pockets for a flask to pass around, providing their friends with a taste of liquor, perhaps pouring a shot into a mixer they bought at the bar inside. The moon shines down on the dancehall, a lone building surrounded by a dirt field–kept bare by the weekly influx of wagons and horses. Voices inside and outside the hall raise up–loud and boisterous, soaring carefree on Saturday night.

The history of the organized dancing locations in South Louisiana begins with the bal de maison, or house dance, which date back to the 1700s, before the arrival of the Acadians. These were intensely local affairs that were held at both grand plantation homes and small farmhouses. Since these events were primarily invitation only, a courier on foot or horse spread the word that a dance would be held that weekend. Bal de maison hosts cleared part of the house so that couples could dance and onlookers could supervise and gossip. The windows were opened for air to flow freely and so that the music could be heard outside. The band was usually a local duo playing fiddles and later accordion. These events were hugely popular, both with affluent landowners and farming families.

Dancehalls, or les salles de danse, became popular in South Louisiana around the time of the Civil War. In many ways, they resembled house dances: paid admission, food and drinks for sale, entire families welcome, largely insular community affairs. Unlike house dances, dancehalls were separate structures open on a regular basis for entertainment. They were open to anyone who could pay to enter, which allowed the evening’s entertainment to be frequently disrupted by arguments and fights about standing personal and family issues.

Some early dancehalls were similar to shopping centers in that they were multi-use facilities. Dauphine’s Dancehall in Parks featured a baseball diamond, a bar, a grocery store, and an ice cream parlor. Richard’s Casino (also known as Tee Maurice) in Vatican featured a dirt track behind the hall that was used for both horse and car races. Lee Brothers Dancehall in Cutoff featured a barbershop and small general store. Also, many halls began as grocery stores or saloons and over time became exclusively dancing and drinking establishments.

The majority of classic-era dancehalls share several common characteristics. The windows could be propped open to allow for unrestricted airflow. In the days after electricity reached these halls, giant fans were installed into the walls to keep air moving. Some of these fans featured a reservoir that allowed a trickle of water to drip onto a curtain of moss for maximum cooling effect. Many people have commented that even without signs, dancehalls were easily identified in the day by the large gravel parking lots and windows braced open to allow cooling and airing out before an event. Typically, women could enter and dance for free, while men paid a charge to dance–a ticket was stapled to their collar upon entering the dance floor. Many early dancehalls featured a “bull pen” for the men–a holding area where they congregated when they weren’t dancing. Later, this area would be replaced by a barroom that served as a shared area for both sexes. Another common feature of halls was a bleacher-style seating area for women. This seating area allowed an unobstructed view of the dance floor for mothers and grandmothers to watch every move of the younger female family members as they danced and talked with young men. Many of these establishments featured a parc aux petits, a room where babies were allowed to sleep, away from the noise and bustle of the hall. Another common feature was a room set aside for playing cards, bingo, and later slot machines.

Although the majority of local dancehalls of recent memory feature Cajun and zydeco music, historically establishments that represented many more genres of music were popular all over the state. Blues, big band, string band, jazz, country and western, rhythm and blues, swamp pop, and rock and roll music all had a home in Louisiana dancehalls. Forty-six of Louisiana’s sixty-four parishes featured dancehalls at one time or another. These halls were established in a variety of settings as well–city centers, rural locations, at water’s edge (and sometimes on the water!), the outskirts of town, and neighborhoods.

The modern dancehall has few persisting characteristics from the old style. The “bull pen” area where single men waited between dances and the bleachers where mothers and grandmothers sat to closely watch the courting couples talk and dance are long gone–replaced by a large bar area and tables to be used by all. Courting is still a major function of the dancehall, even though the discerning eye of the once ever-present chaperones are no longer there to help monitor the behavior of the young single dancers. The gaming rooms are also a thing of the past, replaced by pool tables or one electronic slot machine in a corner, maybe a video poker machine at the end of the bar in place of the card tables that once held endless streams of bourée and euchre games. The things that have persisted are universal: music, dancing, and fellowship.

Although the majority of these famous institutions have closed for good, a few dancehalls remain open today. The changing tides of popular music, the rising popularity of casinos, the raising of the drinking age from eighteen to twenty-one, and the aging population of dancehall enthusiasts all played a part in the decline in dancehall numbers. Sadly, no Louisiana organization exists to preserve, support, and celebrate these cultural icons.

Whiskey River

The first time you take a Sunday drive to a dance in Henderson, you may wonder what you’ve gotten yourself into. A long ride south down Henderson Levee Road leads to a wooden sign emblazoned with a red, white, and blue accordion. It beckons you up and over the levee, revealing the Atchafalaya Basin. Local and visitors alike pause to take in the sight of the largest swamp and wetland in the United States, dotted with houseboats, cypress trees, and birds on the wing. At the foot of the levee sits Angelle’s Whiskey River Landing, affectionately known to locals as simply Whiskey River.

Although Whiskey River seems as if it has been there forever, the dancehall portion of the building was built somewhat recently. Originally a boat launch that added a shaded back porch for fishing contest weigh-ins, the back porch dancehall area was framed in and the space began hosting an occasional dance. After the addition of large fans, the dances became more popular until the growth of the dance crowds demanded that air conditioning be added. Now the hall is comfortable no matter the weather.

Some of the most popular Cajun and zydeco bands play at Whiskey River regularly, which can bring large crowds. Because it can sometimes take a while to negotiate the throng and get a round of drinks, the bar came up with a great solution–a bucket of ice containing six beers. A bucket of beers is cheaper than buying them individually, saves you time spent in line, and even provides a way to keep your beer cold while you dance. Although Whiskey River doesn’t sell food, often a truck selling sausage poboys and hamburgers is parked right outside the front door (ask for the Jack Miller’s BBQ sauce)–helping dancers to keep their energy up and for others, something to soak up excess alcohol.

On, or near, water seems an ideal location for dancehalls and bars, and Whiskey River is no exception. Over the years, numerous popular halls such as the Lake Shore Club on Lake Arthur in Jefferson Davis Parish, the Rainbow Inn on Pierre Pass in Pierre Part, and the Club Sho Boat on the Bayou Teche in New Iberia have drawn on the allure of nearby water as an added attraction. It isn’t uncommon to see a group arrive by boat, often with fishing poles stowed and beer in hand. On one occasion, I saw a fisherman in overalls and white shrimp boots two-step with an imaginary partner all the way to the launch as his partner guided the boat to the dock.

As the afternoon light begins to fade, the sky takes on muted tones of pink, orange, and blue, creating a picturesque backdrop for the band, which plays in front of a large picture window looking out over the Basin. As daylight dissolves, the band announces it is about to begin the last song of the night. In keeping with Whiskey River tradition, patrons, mostly women, begin to climb up on the back bar for one final dance. The whole room, band included, watches–their eyes glued–as the dancers enjoy the brief attention on the elevated pedestal. The regulars all say their good-byes–knowing they will see each other next week–same time, same place.

The dance over, cars begin to climb the levee and head home. A Sunday dance at Whiskey River definitely starts the week on the right foot.

Vermilionville Performance Center

Along the banks of the Bayou Vermilion rests the Vermilonville Living History Museum and Folklife Park, a large complex exhibiting various styles of historic buildings, a garden of healing plants, interesting exhibits, and master craftsman demonstrations. A visit during normal hours (Tuesday through Sunday, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.), yields an impressive array of artisans scattered about the grounds, displaying traditional techniques ranging from cooking food, spinning cotton and weaving to woodworking and playing Cajun and Creole music–truly something of interest for everyone. One of Lafayette’s premiere cultural attractions, Vermilionville also boasts a dancehall. The bal du dimanche, or Sunday dance, is held 1-4 p.m. weekly in the Performance Center.

The building was modeled after an old time cotton gin and features a large wooden plank dance floor and a high ceiling with exposed beam rafters. The raised stage and modern sound system ensure that the band can be enjoyed from every seat in the house. The central dance floor is flanked on both sides with wooden tables and ladder-backed chairs (some of which were made by Cajun music legend D.L. Menard). The walls are adorned with colorful local quilts, the Acadian flag, and iconic images of local Louisiana music legends and storied dancehalls–a subtle salute binding the past and present together. When weather permits, the rear walls can be folded away, creating an open-air barn feel that allows the music to fill the area around the hall.

The traditional Cajun, Creole and Zydeco music offered by the bands that play at Vermilionville bring out a widely varying crowd. Locals and tourists, Creole cowboys in pressed jeans and big belt buckles, college-age girls in short denim skirts, cowboy shirts and boots, zydeco devotees in tie-dye, head bands, and sandals, and Paw-Paws in one piece jumpsuits and Maw-Maws with freshly set hair all crowd onto the dance floor at the same time. It’s no wonder–the bands on the schedule are all crowd favorites–Creole legend Goldman Thibodaux, Swamp Pop crooner Warren Storm, zydeco headliners like Geno Delafose and French Rockin’ Boogie, classic Cajun groups like the Ray Abshire Band, as well as extremely popular younger groups like Bonsoir, Catin, The Revelers and Soul Creole all keep the dancers coming back for more.

The dance floor begins to populate just after the band fires up–soon it is a waltzing mass moving in a large counterclockwise ring in time to the music. The men leading, an occasional pair of clasped hands rise above the crowd as a couple twirls. The corners of the floor are sometimes occupied by a dance lesson, a grandparent dancing with a child, or isolated couples that have opted out of the giant spinning swirl in favor of their own style of dance.

This weekly event is one of the only all age, smoke-free dance experiences currently in Acadiana and possibly the whole state. A bar in the rear serves both alcoholic and non-alcoholic drinks and sometimes food is offered for sale. The historic setting, spacious dance floor, community feel, and great music make a Sunday afternoon at Vermilionville a real treat.

La Poussière

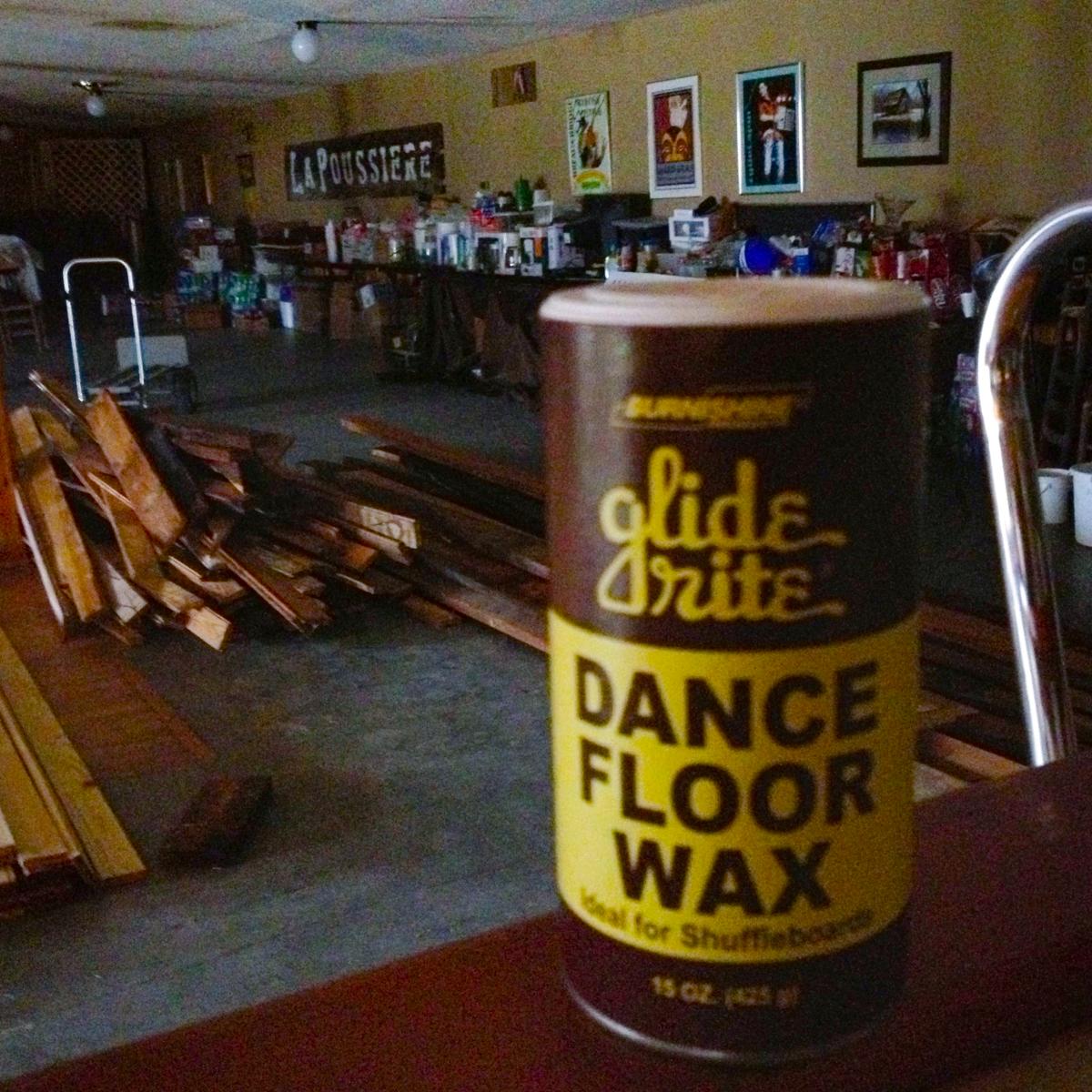

On January 10, 2013, a tornado peeled back the roof of the La Poussière dancehall. The damage was extensive–water logged ceiling, busted sheet rock, roof, rafter, and electrical damage…

La Poussière

On January 10, 2013, a tornado peeled back the roof of the La Poussière dancehall. The damage was extensive–water logged ceiling, busted sheet rock, roof, rafter, and electrical damage, as well as destroying the entire kitchen. Facing thousands of dollars in repair bills, the owners, Lawrence, Judith, and Nicole Patin were distraught. The hall is a family tradition started by Lawrence’s parents in 1955. Running a dancehall had always been a time consuming second job for the family, so immediately after the storm they were faced with a tough decision–whether or not it was time to close down La Poussière for good.

Unknown to the Patins, a plan to cover the repairs was hatched before the damage was even assessed. A few of the musicians who consider La Poussière a second home got on the phone and arranged a benefit concert with an all-star lineup. By the following Monday, local companies had started the repairs. In less than one month the doors were once again open for business. Held on February 2nd, the benefit–dubbed “The Welcome Home Celebration”–was a twelve-hour dancing marathon. Artists donating their time and talent to the cause included Jackie Callier and the Cajun Cousins, Geno Delafose and French Rockin Boogie, Cheryl Cormier and Cajun Sound, High Performance, Walter Mouton and the Scott Playboys, and Steve Riley and the Mamou Playboys. Over the course of the day, over eight hundred people came to honor La Poussière and witness it made whole again. The response was so great that it was almost necessary to dance in shifts.

For over forty years, Walter Mouton and the Scott Playboys appeared weekly at La Poussière, which means “The Dust” in Louisiana French, for their Saturday night dance. Mouton is famous not only for his longevity, but for the fact that his well-known band does not have a large recorded output–only a few scarce songs can be found on commercial releases. This is because they consider themselves a dance band–many longtime regulars at La Poussière can attest to this fact. Probably for this reason, La Poussière and Mouton are forever linked.

La Poussière is a long rectangular hall with the majority of the floor space dedicated to the dance floor. Along the wall and edge of the dance floor are tables, many designated as reserved by a plastic sign holding the name of a regular. Those regulars, mostly older, make a weekly trek from all over the southern portion of the state to visit and dance. The old time atmosphere, great Cajun music, a colorful cast of regulars, and the well-worn dance floor make a trip to Breaux Bridge to visit La Poussière a genuinely good time.

La Poussière features live music from various popular local Cajun bands every Saturday night around 7 p.m. Every Sunday afternoon at 2 p.m., Jackie Callier, Ivy Dugas and the Cajun Cousins play. They have their own unbroken streak going of playing once a week for almost 15 years! It is also worth noting that all events at La Poussière are smoke free.

El Sid O's

Make your way to the corner of North Saint Antoine and Martin Luther King Jr. Drive and you’ll be at a spot that has inspired many visits to Lafayette. During the day, the building…

El Sid O's

Make your way to the corner of North Saint Antoine and Martin Luther King Jr. Drive and you’ll be at a spot that has inspired many visits to Lafayette. During the day, the building itself is a beige painted cinder block and brick, mainly recognizable because of the canopied front entrance that reads simply “El Sid O’s.” Located in the historic Lafayette Truman neighborhood, El Sid O’s Zydeco and Blues Club has been drawing crowds since it opened on Mother’s Day 1985.

Owned and operated by Sidney “El Sid O” Williams, member of one of the founding families of zydeco and brother to zydeco star Nathan Williams. Sid is an accomplished accordion player in his own right, as well as a well-known local businessman (he also owns Sid’s One Stop, a convenience store just down the street). The annual Thanksgiving food drive show at El Sido’s (now in its 28th year!) is legendary, having featured a who’s who of zydeco including Boozoo Chavis, Buckwheat Zydeco, Beau Jocque, Nathan Williams, Rockin’ Dopsie, Keith Frank, Horace Trahan, Terrance Simien, and many more.

A visit to El Sid O’s is always memorable. Upon entry, zydeco music is already playing on the sound system, interrupted at regular intervals by Sid, breaking in from a microphone he keeps behind the bar. The messages are half announcements about upcoming shows or the band of the evening and half a pitch for drink specials, but it is understood that Sid not only runs the show, but is a part of it. Regulars and visiting musicians alike seek him out to pay homage upon entering. At some point in the evening, Sid, wearing a black cowboy hat, comes from behind the bar to visit all around. A gracious host, he introduces himself throughout the seating area, making sure that everyone has what they need and are comfortable. Décor includes beer and liquor signs, as well as banners and posters from events past and future.

As the club begins to get crowded, the band takes the stage. Sound levels are checked, and after Sid’s brief word of welcome from behind the bar, the accordion bellows breathe and come to life, beckoning the other instruments to join in. Sound fills the room, and a wave of activity begins as couples get up from their seats to fill the dance floor. Over the course of the night, several accordions might be used, from the oversized piano type made popular by Clifton Chenier to the older, more traditional diatonic button variety. The stage lights are reflected in the instrument’s polished finish as the accordionist moves in time to the music.

Zydeco dancing can be a magical thing to watch. Despite the basic steps, every couple makes it their own, adding personal flourishes and gestures until the basic underlying structure is not the primary focus anymore. Dance styles range from dancing in place with barely perceptible movement of the feet with very little upper body action, to a wide ranging swing style that involves partner twisting, synchronized side-stepping, and small jumps. The faces are often stoic as they complete complicated dance moves, seemingly effortless and in sync. Examining the multitude of styles on display at any one time can be hypnotic.

After about an hour and a half, the band puts down their instruments and stops for a well-deserved break. The dancers need it too. Sid gives a call over the microphone for a round of applause and reminds us that this short break is a great time to get an ice-cold beer. Music is pumped through the PA system again, and suddenly the dance floor is filled with a zydeco line dance interlude. Maybe I was wrong about the dancers needing a break. It’s getting close to midnight and El Sid O’s still has a lot of life left in it.

Paul's Playhouse

Fifty years as an established business is quite a feat. It is even more impressive when the business is a bar and dancehall that is relatively unknown in the surrounding areas. The…

Paul's Playhouse

Fifty years as an established business is quite a feat. It is even more impressive when the business is a bar and dancehall that is relatively unknown in the surrounding areas. The Playhouse in Sunset is one such spot.

Owner Almo “Chickeen” Miller sat quietly behind the person taking the entrance fee, getting up every few minutes to shake hands and greet attendants. It happened that this night, in addition to being the fiftieth anniversary of the club, was the seventy-fourth birthday of the owner. He wore a suit coat studded with gifts of pinned on cash-anything from fives, tens, and twenties, on up to a single hundred dollar bill.

It was 9:30 p.m., the posted time for the evening’s entertainment, Patrick Henry and the Liberation Band, to begin. I should have known better–it would be almost two hours before the first note was struck. Before then, I had friends to make and cold two dollar ten-ounce beers to drink.

A DJ played recent local R&B and zydeco hits, the growing crowd occasionally pairing up to dance. The Playhouse, previously called Paul’s Playhouse, is a bona fide rhythm and blues and zydeco dancehall. Among the legendary performers who have graced the stage are local Grammy winners Clifton Chenier and Stanley Dural of Buckwheat Zydeco fame, as well as legendary Texas performers Barbara Lynn and Archie Bell and the Drells.

One of the clubs that brought in touring bands off the “chitlin’ circuit,” the Playhouse helped inform the distinctly Louisiana music genre of Swamp Pop. The contents of the CD jukebox trace the history of the club itself, with albums by blues icon Bobby Blue Bland, mid- 60s funk soul by Joe Tex, the latest offerings from nouveau zydeco artist Chris Ardoin, “Zydeco Boss”–Keith Frank, as well as no less than six albums by the evening’s entertainment, “Mr. Excitement”–Patrick Henry.

A freshly roasted suckling pig was delivered to a nearby table, directly under a “Coors Light“ pool table light advertising beer, as I perused the jukebox contents. The party was picking up speed. By the time the band started the room was getting crowded, old friends and acquaintances exchanging greetings as they flooded in, some bearing offerings for the growing food table and others delivering bills to Chickeen’s suit coat.

The sound of a high-energy hyped-up introduction filled the room while the very tight band pumped up the entrance of “Mr. Excitement.” As Patrick Henry made his way through the crowd, he picked up speed, almost bursting onto the stage when he arrived. His appearance sent a wave of energy careening through as the entire room rose to their feet. The Liberation Band went into a James Brown song and the dance floor filled followed by a string of Henry’s own songs that kept the crowd at full attention and dancing. Folks were still arriving at midnight.

In a moment of sheer delight at the entire scene, I was overwhelmed by the belief that The Playhouse might be here for another fifty years, and that I hoped it didn’t need to change one single bit to make it work.

Blue Moon Saloon

Tucked away just one block off of one of Lafayette’s busiest thoroughfares is a special place: 215 E. Convent Street. In 1900, the large wooden-framed house that currently occupies this…

Blue Moon Saloon

Tucked away just one block off of one of Lafayette’s busiest thoroughfares is a special place: 215 E. Convent Street. In 1900, the large wooden-framed house that currently occupies this spot was relocated from downtown and, through the years, has served variously as a private residence and flower shop. It now operates as the Blue Moon Saloon and Guesthouse. Following in a long line of Louisiana bars and dance halls before it, the Blue Moon (as it is commonly referred to locally) has a diversified business plan–in this case, a location where both a bar as well as a dance hall and guesthouse cohabitate. People from all over the world have stayed in the Blue Moon’s five guest rooms alongside local and touring bands from all genres who have graced the stage.

Opened in 2002 by friends Catherine Schoeffler and Mark Falgout, the Blue Moon was modeled after hostels they experienced abroad, and the concept quickly caught on. It filled a void in the Lafayette scene, allowing locals a fun, new open-air venue and dance spot as well as a dynamic place for travellers to stay. The two things intertwined well, allowing visitors to experience local culture in a literal backyard, while locals enjoyed a revolving cast of characters to share their culture with. After a short time with a makeshift stage, the crowds had outgrown the space, demanding more room for dancing and sitting, which propelled the expansion of the deck and permanent bar area to accommodate the growing club-goers. The resulting additions have come in leaps and bounds, and the crowd has kept coming too. The Blue Moon now boasts an additional bar near the entrance and a deck complete with a seating area in the side yard, which is used for special events, such as wedding receptions, book signings and food service.

The Blue Moon began as a venue for locals and many notable local bands have played there at one time or another. Highlights of that extensive list include Bonsoir Catin, Feufollet, Roddie Romero & the Hub City Allstars, Steve Riley & the Mamou Playboys, the Pine Leaf Boys and Cedric Watson and Bijou Créole–all Grammy nominees. Chubby Carrier and the Bayou Swamp Band and Terrance Simien were also Blue Moon performers who won Grammys. Additionally, local favorites Al Berard and the Berard Family Band, Balfa Toujours, the Bluerunners, Creole Zydeco Farmers, David Egan, The Figs, Hadley Castille, Harry Hypolite, Horace Trahan and the Ossun Express, Jeffrey Broussard & the Creole Cowboys, Lost Bayou Ramblers, the Magnolia Sisters, Marc Broussard, Nathan & the Zydeco Cha Chas, The Red Stick Ramblers, the Savoy-Doucet Cajun Band, Curley Taylor and Louisiana legends the Hackberry Ramblers have all graced the Blue Moon stage.

Although the Blue Moon’s first steps into music were decidedly local, it did not take long for touring bands to start making it a regular stop. Folk artists, including The Mammals and The Duhks, as well as Texas acts The Weary Boys, Scott H. Biram, Dale Watson, The Gourds and even legendary songwriter Billy Joe Shaver have all played to sold out crowds. Guitar gods Bill Kirchen, Dick Dale and AM radio royalty Susan Cowsill have all additionally performed several times on the crowded back porch. Even more thrilling were the performances of New Orleans genre mixers The Iguanas, piano champions Henry Gray and Henry Butler, jazz funk guitarist Leo Nocentelli of The Meters and the Rebirth Brass Band.

Although the primary music genres performed have been roots rock-oriented, the Blue Moon has since grown to feature many styles of music. A recent mainstay has been performances by indie rock bands. Over the years, there have been shows by FM radio breakouts Givers, New Orleans dance punk organist and puppet show Quintron and Miss Pussycat, new wave rockers Bas Clas, local indie heroes Brass Bed as well as a string of classic shows by Lafayette rockers Matt Rock & the PowerBoxx.

Larger local festivals have brought many memorable musical acts to the Blue Moon. Bands from Festivals Acadiens et Créoles have even offered occasional full-length late night sets that collaborate with the Saloon’s “Rhythm and Roots” series, which partners local favorites with visiting international bands from Festival International de Louisiane. Additionally, the club’s location, just off the Lafayette parade route, makes it especially hopping during Mardi Gras, when in previous years, they have hosted an all-day party with food for sale and a day long schedule of bands.

Inevitably, the Blue Moon has become a community gathering spot. No other time is it more evident than the free Cajun jam, held every Wednesday night. The jam offers an opportunity for musicians to meet and play together, regardless of their skill level. It is not uncommon to find master Cajun musicians at the jam, sitting side by side with novice players. Furthermore, the Blue Moon has been home to numerous events, such as the Nue Moon Revue, which features a revolving cast of community members performing their own songs while backed by an all-star band, the BluesBerry Festival, celebrating blueberries and the blues, various “Hoot Night” concerts, a kind of live band karaoke which invites audience members onstage to sing vocals on well-known bands or Christmas tunes and Acadiana Vinyl Haul, which turns the Saloon’s entire exterior property into a short-lived record swap.

In 2014, it was no surprise that the Blue Moon Saloon and Guesthouse was named one of the “Top 100 Bars in the South” by Southern Living magazine. With a full-service bar, excellent music and small stage butted up against a cozy dance floor, a night at this beloved venue is an intimate experience with friends, even if you are just meeting them for the first time. It feels relaxed, welcoming and homey, like sitting on a friend’s back porch–and that’s what it is–Lafayette’s back porch.

Fred's in Mamou

Open only on Saturdays, Fred's is a once in a lifetime experience.

Fred's Lounge

Getting up early on a Saturday morning for a visit to Fred’s Lounge in Mamou feels like embarking on a first light fishing trip–but with a very different end in mind. Driving the quiet state roads en route, you pass through serene countryside. The wide open plains, carved up into farming fields and home plots, are interrupted by the occasional stand of trees, breaking up the cattle, crawfish and rice fields on either side of the road.

As you approach Fred’s, you can feel the excitement growing. The side has a large mural proclaiming “Mamou–Cajun Music Capital of the World.” The band inside has already begun, and you struggle to make out a barely discernable tune, muffled as it makes its way through the building’s brick and cinder block walls. As you open the front door, you get your first peek inside the busy space: A man who has been leaning against the inside of the front door almost falls backward onto the sidewalk outside and there’s a crowd of people behind him inside, elbow-to-elbow, drinking and talking. Beyond them are a dozen or so bobbing heads of couples dancing, and through the darkness, you can make out the band, roped off in the center of the room to protect them from being bumped by the dancers. Framed posters–advertising politicians, festivals and other events from years past–line the walls. A string of green, gold and purple flags advertising beer hang from the ceiling around the band area. The air is thick with smoke. As you stand in the open doorway, music blaring and sunlight streaming in, it is time to push through the dark, crowded room and make your way to the bar. You’ve made it. You’re at the famous Fred’s Lounge in Mamou.

Given that the bar opens at 8 a.m., it is not surprising to see many patrons drinking their breakfast. The most popular drink orders seem to be a Bloody Mary and (often two at a time) 10 ounce beers. A morning at Fred’s is very crowded, so making small talk with your new neighbors while waiting to get the attention of a bartender is encouraged. Fred’s is a destination spot for people from all over the world, so there is no telling who you might meet. Behind the bar, T-shirts are displayed for sale in a variety of colors–all featuring a reproduction on the back of a sign fashioned years ago as a plea to the occasionally overexcited patrons: “Please DO Not Stand on the Tables, Chairs, Cigarette Machine, Booths, and Juke-Box! Thank You. Fred.”

The namesake of this fabled spot is Alfred “Fred” Tate, a Mamou native, who bought Tate’s Bar in late 1946 and rechristened it Fred’s Lounge. It quickly became a popular spot in downtown Mamou, a small town that was, and still is, well-known for its watering holes. It is said that in those early days, the bar was opened six days a week and always packed with locals. Tate passed away in 1996 and a plaque honoring him is on the wall just outside the front door.

The current face of Fred’s is Sue Vasseur–known to most as “Tante Sue from Mamou.” Vasseur, Fred Tate’s ex-wife, is now in her mid-80s and can be found behind the bar most Saturday mornings–wearing a Fred’s Lounge T-shirt emblazoned with an accordion on the front that she sometimes pretends to play, pinching the sides and squeezing it back and forth in time with the music. When the band strikes into “La Danse de Mardi Gras,” Tante Sue leads a procession around the crowded bar and insists that patrons join in. All along, she stops to hug old friends and strangers alike, posing for pictures and making small talk. On her belt is a holster that holds a flask filled with cinnamon schnapps that she occasionally passes around to patrons who would like to take a shot with her.

In the period after WWII, Fred’s Lounge, and other places like it, became a haven for local Cajun culture. As radio, television and film began to increase in popularity, many Cajuns felt pressure to assimilate into the increasingly standardized culture that dominated the United States. As a result, some groups in small towns, like Mamou, held even tighter to tradition. For example, the plan to revive the Mardi Gras Courir tradition in Mamou, a masked rural procession to beg neighbors for communal gumbo ingredients, was hatched at Fred’s in the early 1950s.

Even with all the documented history, no one is exactly sure when the Saturday morning band tradition started. What we do know is that it has been a weekly mainstay on local radio airwaves since 1962. High school teacher and Cajun cultural activist Revon Reed pitched the idea to Tate as a 15-minute live Saturday morning broadcast from Fred’s Lounge on Ville Platte radio station KVPI (1050 AM). Once the original concept of live Cajun music, announcements and advertisements in French became a hit, the show quickly grew into the two-hour-long program that it is today. Reed passed away in 1992, but the show is still going strong, every Saturday from 9-11 a.m.

Needless to say, the Saturday morning event as well as the culture documented at Fred’s has certainly made this hot spot well-known to enthusiasts and students of Cajun culture. In fact, Louisiana folklorist Barry Ancelet recorded legendary collaborative and spontaneous folktales or “Pascal Stories” at Fred’s that were spun by Mamou locals. The Saturday morning band has featured legendary Cajun master musicians Nathan Abshire, Dewey Balfa and Sady Courville as well as contemporary supergroups, such as Balfa Toujours and the Lafayette Rhythm Devils. Several important documentaries were also shot on location at Fred’s, including Alan Lomax’s 1991 film Cajun Country.

Clearly, it is easy to have a memorable time at Fred’s Lounge. Visitors get pulled onto the dance floor to try out the two-step, the bands are good and the drinks are fairly priced. Camaraderie is created among those in attendance–drinking and dancing early on a Saturday feels a little like breaking the rules. It is hard to believe that when last call comes, it is only 1:45 p.m. You close your tab and make your way out the door, squinting in the daylight. The crowd scatters, some to their cars, some to lunch spots nearby and a few are even headed to other bars whose doors have just opened and bands are just starting up. Fred’s is only open for six hours each week–every Saturday morning from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m.–so be sure to set your alarm and check them out.

Grant Street Dancehall

If you ask around about well-known dance halls in Lafayette, it won’t take long before someone mentions Grant Street Dancehall. Located downtown, just off of Jefferson Street, this…

Grant Street Dancehall

If you ask around about well-known dance halls in Lafayette, it won’t take long before someone mentions Grant Street Dancehall. Located downtown, just off of Jefferson Street, this famous venue has had a colorful past, hosted many celebrated musical acts and has recently been taken over by new owners.

In 1880, the railroad arrived in Lafayette, then called Vermilionville. Many structures were erected near the tracks to service the arriving passengers and products, including the building that now houses Grant Street Dancehall, built in 1898 as a storehouse for fruit. This cypress building, with its open rafters and wide planked floor, which has since been scarred by years of moving pallets and hand trucks across it, served as a warehouse of one kind or another until 1980, when it turned into a dance hall.

Grant Street Dancehall opened on the Fourth of July, 1980. Original owners Mike Hanisee and Loren Farmer booked a sure thing for the grand opening: Clifton Chenier and His Red Hot Louisiana Band as the headliner and the Red Beans and Rice Revue as the supporting act. The club was packed and quickly turned into Lafayette’s premier venue to see bigger local acts as well as a regular stop for national and regional bands on tour.

Some of the local acts who played at the club include punk rock and roll heroes Frigg A-Go-Go, slide guitar wizard Sonny Landreth, zydeco ambassador Buckwheat Zydeco and swamp pop supergroup Lil’ Band O’ Gold. Grant Street also hosted legendary touring bands including Stevie Ray Vaughan, Ray Charles, Muddy Waters, J.J. Cale, Marcia Ball, B.B. King and “the Killer” Jerry Lee Lewis. Grant Street is also well-known for hosting numerous fundraisers, benefits and even birthday parties. On occasion, other types of events, such as midget wrestling matches, have additionally been held at this popular hangout.

By 2000, Grant Street changed hands several times and had gone through several different managers, keeping the club open only intermittently. The club even appeared for sale in the local classified ads. Despite all that, the venue is once again up and running featuring live music.

At the beginning of 2017, Grant Street Dancehall hosted a birthday party for guitar master Paul “Lil’ Buck” Sinegal in the smaller side room called “The Saloon.” Sinegal has had a long and illustrious career, from recording as a session musician for Excello Records in the 1950s, fronting his own rhythm and blues band Lil’ Buck & the Top Cats in the early ‘60s. He was also a sideman with Clifton Chenier for 10 years starting in the late ‘60s, followed by playing alongside Rockin’ Dopsie and Buckwheat Zydeco. Even though he is mainly known as a zydeco musician, Sinegal maintains that he really plays blues guitar. And his party at Grant Street was no exception, as he effortlessly tore through blues standards and R&B favorites, thrilling the crowd and inspiring dancing, from wild spinning to a slow drag.

Lil’ Buck wielded his guitar like a craftsman with a tool, never pausing to look around for reference–his hands knew exactly where they were and went to the next spot with ease and fluid motion. His band, a four piece, was spot on from years of this style of loose playing–no practice needed. The sound bouncing off the brick walls, mixed with a small but colorful light show, was intoxicating.

As the crowd rolled in, Lil’ Buck’s band continued to play as a few university students paused to listen from outside the open front door of the club, then turned to head downtown where cruising and drink specials rule the night. Just then, a car with two older couples pulled into the lot. As they got out, one of them said loudly, “I can’t believe this! Lil’ Buck at Grant Street!” As they danced toward the front door, you couldn’t help but smile. Grant Street Dancehall is indeed back.

Grant Street Dancehall

If you ask around about well-known dance halls in Lafayette, it won’t take long before someone mentions Grant Street Dancehall. Located downtown, just off of Jefferson Street, this…

Holiday Lounge

Driving north out of Eunice on Louisiana Highway 13 at night, the Holiday Lounge, on the outskirts of Mamou, will get your attention. A beacon of red and yellow neon appears reflecting in the smooth waters of a seasonally flooded crawfish pond that rests between the road and the club. Some of the lights have burned out or broken over the years, but it still calls to you across the darkened landscape of the Louisiana prairie.

By the mid-1950s, rock and roll music was established as an incredible new cultural force, but the young people of Mamou and surrounding area had no place to dance to it. Local jukebox operator Ed “T-Ed” Manuel already owned several other bars that featured live Cajun music regularly but recognizing an untapped crowd, he built the Holiday Lounge for the purpose of entertaining the young folks.

T-Ed’s son, Eugene Manuel, still remembers the neon sign being installed on the building’s colorful exterior. “When they put that neon on, they plugged it up and [the neon lit in motion] went from the middle to the outside. Daddy stood out front in the dark and watched it light up. As soon as it did, he started yelling. He told the sign man, ‘No, no, no! Reverse the action–that motion is telling the people to go away–I want it to draw the people in.’ He fixed the sign and sure enough, it brought the people.”

One can imagine the Lounge didn’t look like any other building in the area in 1958–or the present. The decorative style is decidedly tropical, with the exterior walls featuring painted palm trees that are now almost engulfed by the live banana trees growing right in front of them. An exterior hallway that divides the bar from restaurant (long-closed) features hand-painted tropical fish on a deep aqua background. The Holiday Lounge’s exterior colors may all be bleached out by years of direct sunlight, but the interior is a world of vivid visuals untouched by time. The ceiling features gold stars of various sizes, strands of Christmas lights and long fluorescent black light tubes. The lights give an unworldly glow to a host of neon-painted wooden cutouts of women in bathing suits along the club’s walls–most with bouffant or beehive hairdos that reveal the era they were originally painted and installed. Booths along one wall are semi-circular and covered in vinyl. A small dance floor fills one corner of the room. A mirrored wall behind and pulsing lights below give it a go-go feel. Much of the décor, inside and out, of the Holiday Lounge is a South Pacific theme, a nod to T-Ed Manuel’s time in the Merchant Marines during WWII.

Eugene hauls out the original jukebox from a back room for special occasions, like when patrons from the old days stop in. “I’ll plug it in and spin a record. It’ll make them stay for one or two more drinks after they say they are leaving. You see, even though the Holiday was built for the younger crowd, I always liked hanging out with the older people and listening to French music. I grew up speaking French so lots of people my age were trying to get away from that. Old people who would sit and visit only speaking French–you could really learn a lot from them.”

For years, the Holiday has not regularly featured live music. Even so, it is so legendary that it has inspired several songs, including “Le Holiday” by the Cajun supergroup Charivari on the 2005 album A Trip to the Holiday Lounge as well as Steve Riley & the Mamou Playboys’ Party at the Holiday, All Night Long! It still opens five or six nights a week for a small, dedicated crowd or regulars. Recently, musician and part owner of the record label Valcour Records, Joel Savoy brought a band he was working with to the Holiday for a drink after a recording session. The band fell in love with the club and asked if they might play there sometime. Eugene eagerly agreed.

The band, Kyle Huval and the Dixie Club Ramblers, packed the Holiday Lounge on that initial gig. The crowd consisted of people from near and far, regulars and first time attendees. As they played, the band cooked a gumbo just off the stage and around the corner by a pool table, which they served to the crowd when they took a break. Eugene even had to go and get more beer. It was a special sight to see the club so busy. The night was a huge success–so much so that bands may play more regularly.

“Old embers get rekindled–everything old is new again,” Manuel said. “All these people in here–now this is how it used to be all the time. The Holiday Lounge hasn’t gone anywhere. We’re coming up on 60 years here–still family owned-and-operated.”

Southern Club

The stretch of U.S. Route 190 West between Opelousas and Eunice looms large in the history of Louisiana music. The tiny town of Lawtell featured the legendary zydeco clubs the Offshore…

Southern Club

The stretch of U.S. Route 190 West between Opelousas and Eunice looms large in the history of Louisiana music. The tiny town of Lawtell featured the legendary zydeco clubs the Offshore Lounge (open sporadically) and Richard’s Club (still operating and now called Miller’s Zydeco Hall of Fame), rhythm and blues club Teddy’s Uptown Lounge (open) and dance halls the Green Lantern and the Step-Inn Club (both long gone). But the clubhouse of swamp pop, the Southern Club, still stands just outside Opelousas, a roadside monument to remind all of the good times that were once had there.

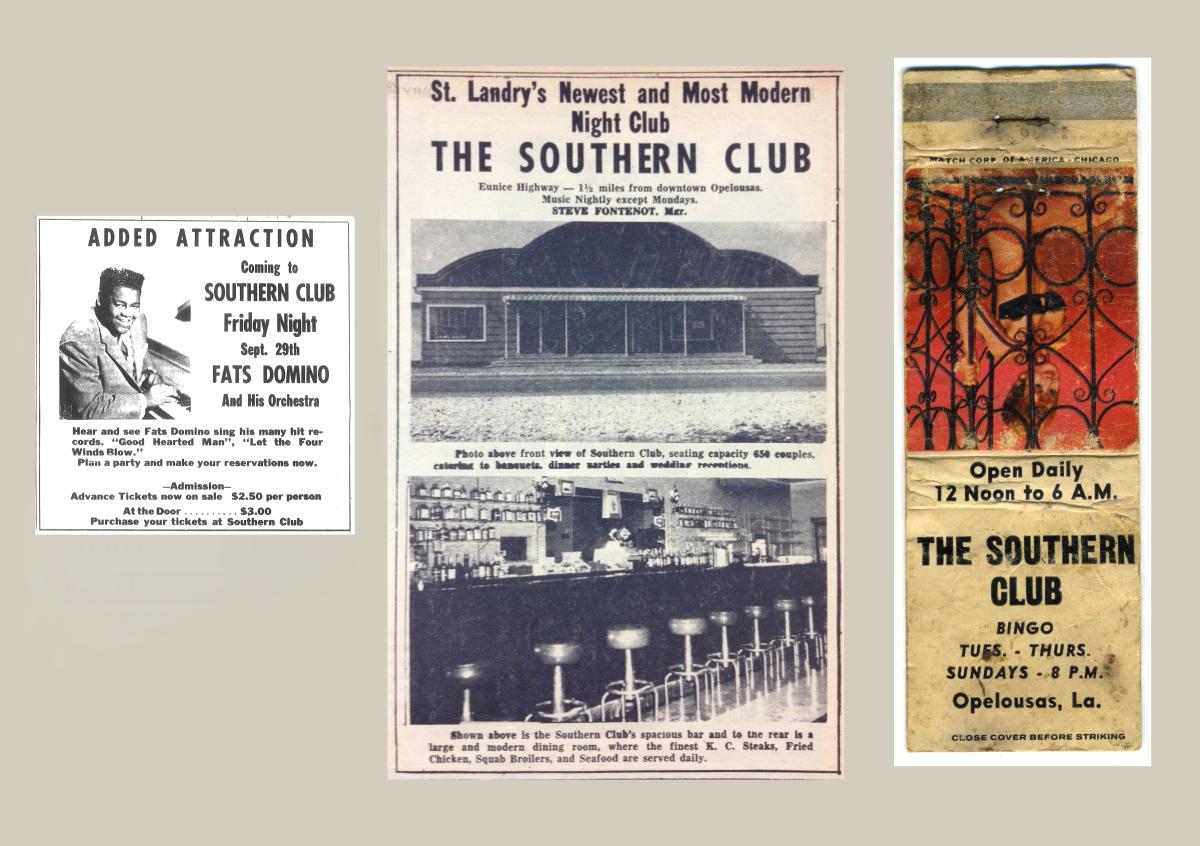

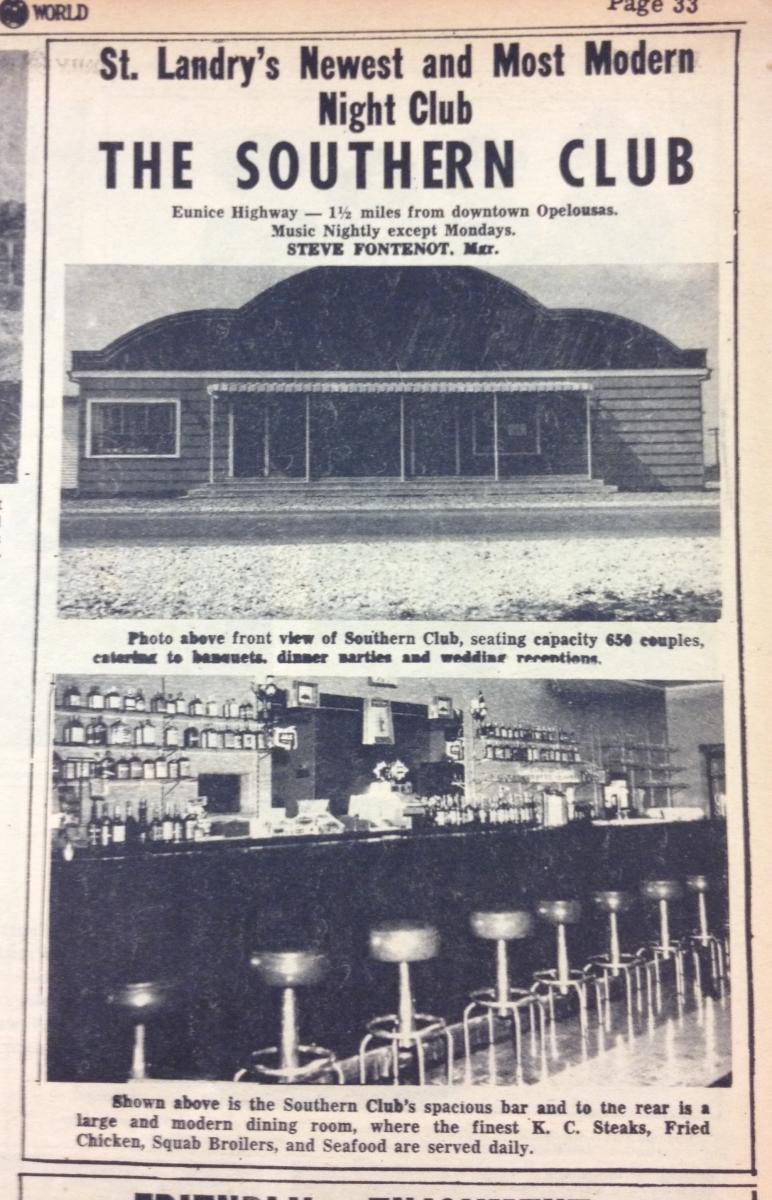

The massive building, which now sits quiet, was once a hub of activity. Built in 1949 as a casino, dinner and dance club by Claude Morein, the Southern Club quickly became a popular spot for a night out. Morein sold out to family after a crack down on gambling, and the business eventually landed with his nephew, Lionel “Chick” Vidrine. The Southern Club had an official grand opening on January 1, 1956.

The Club’s location meant it was a convenient stop for national touring musical acts who were making their way between the New Orleans area and the larger cities in Texas. Rock & Roll Hall of Fame inductees Chuck Berry, Lloyd Price, Jimmy Reed, The Coasters and The Platters have all played onstage. These acts alone certainly made this a notable spot, but the most internationally known band to play the Southern Club was from much closer to home: New Orleans’ own Fats Domino.

Chick’s brother, Rayburn Vidrine, worked at the club for 25 years and saw lots of acts, but his favorite performer to see at the club was Antoine “Fats” Domino. He played the club a half-dozen times, heralded by newspaper advertisements for weeks beforehand, resulting in huge crowds. “Fats was really something to see live,” said Vidrine. “They’d set up his piano on the stage against the wall so it couldn’t get out from under him. People would be dancing everywhere. The place would be packed–turning them away at the door. And it was always fun to drink a little bit with him beforehand. Fats was a really nice guy.” Domino, also a member of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, is best remembered in Louisiana for his piano-styled New Orleans rhythm and blues and influence on the evolving style of music that came to be known as swamp pop.

Swamp pop is a genre of music created by young Cajun and African American musicians in the early 1950s that blended elements of the locally popular traditional French music, New Orleans rhythm and blues, country and western music and the emerging phenomenon of rock & roll. Originating in the Acadiana area, swamp pop was very popular throughout South Louisiana and in southeastern Texas. Swamp pop songs, like Dale and Grace’s I’m Leaving It Up To You and Rod Bernard’s This Should Go On Forever, were so popular that they appeared on the U.S. pop charts. Local acts who regularly graced the Southern Club stage read like the list of artists from a swamp pop greatest hits compilation: Lil’ Bob and the Lollipops, Guitar Gable and the Musical Kings, Johnnie Allan, the Fabulous Boogie Kings and Bobby Page and the Riff-Raffs, with swamp pop supergroup the Shondells (featuring Warren Storm, Rod Bernard and Skip Stewart). Simply put, the Southern Club was the home of swamp pop.

The Southern Club’s massive exterior hints at its spacious interior. The building’s front has three joined arches, which still feature part of the neon that spelled out the club name–although only half of the letters remain, survivors of vandals, beer bottles and rocks in the years since it closed. Entering through the front door, you are met with a large bar that conceals two huge drink coolers that once held over a thousand beers each. An immediate left inside the door takes you to the restaurant area–also used for bingo and bourré, a favorite card game of locals. The area to the right originally housed a coat check and slot machines, but now holds a derelict pool table covered with cigar boxes full of cancelled checks.

Past the bar on the left and through a set of double doors with porthole windows stands the main room. Straight ahead is a massive wooden dance floor, now covered in dust and warped in places, betraying the fact that time has taken its toll on the roof overhead, allowing rain to enter. The dance floor is surrounded by evenly spaced posts, serving not only as building supports, but as a place to hang speakers and call buttons as well–harkening back to the days when waitstaff brought drinks to the tables. To the outside of the dance floor and beyond the posts on both sides of the room stand dozens of tables with hundreds of chairs stacked on top, all waiting to be dusted off and used again. The outer walls have over a dozen sporadic rectangular holes at varying heights, once filled by window air conditioning units that were long ago stolen. These holes are now the only source of light–giving the building the feeling of a sunken ship on the bottom of the ocean. Instead of water, the space is thick with memories of so many glory days.

The gigantic room is anchored at the far end by the main stage. The stage itself is slightly raised, allowing a better chance of seeing the band over the heads of the people on the always-crowded dance floor in bygone years. The stage is wide and deep, a reminder that it once held large orchestral dance bands before the invention of rock & roll and its smaller combos. The ceiling over it has a rounded overhang that once featured a gathered curtain, now long gone. A railing once separated the stage from the lower floor–meant to keep people from inadvertently falling onto the stage as they danced past the bandstand. A second stage to the right allowed for a seamless transition from one band to the next.

In 1994, Chick passed away, and the business operated until the Vidrine family closed it in 1996. Since then, the Southern Club has sat quietly, waiting to be revitalized and put back into service. Currently, an effort to do just that is underway, led by Chick’s brother.

According to Rayburn, “I worked here for 25 years, and I saw a lot of different fads in music, in dress and the way people act. It was an experience that I wouldn’t do again, but I wouldn’t sell it for anything in the world either…I’d really like to see something happen with this building, in honor of my brother, Chick.” As his voice quivered with emotion, Vidrine continued, “He was a kind and generous man who helped everybody who needed it, and this was his place. He deserves to be remembered.”