Eighty years ago folklorists John and Alan Lomax visited South Louisiana to record Cajun and Creole songs to be added to the Library of Congress Archive of American Folk Song (now the Archive of Folk Culture). It was the first time Cajun and Creole songs were captured on tape for archival purposes. In 1964, Dewey Balfa, Gladdie Thibodeaux and Louis Vinesse Lejeune were invited to perform at the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island the first Cajun musicians ever accorded that honor. Balfa didn't know how the South Louisiana music would be received and was surprised that audience members sat and listened, as opposed to dancing like they did back home.

"He (Balfa) noticed how people were sitting down and listening to the music and giving it a certain amount of respect," said Dewey Balfa's daughter, Christine Balfa.

At the end of Dewey Balfa's set, the audience responded with a standing ovation. Buoyed by Lomax and inspired by Newport, Balfa was determined to ignite that same respect and adoration in his home state. He came back to Louisiana with a purpose.

"His goal was to bring home the echo of that Newport applause back to Louisiana," said Barry Jean Ancelet, a folklorist and scholar who is now head of the University of Louisiana at Lafayette's Department of Modern Languages.

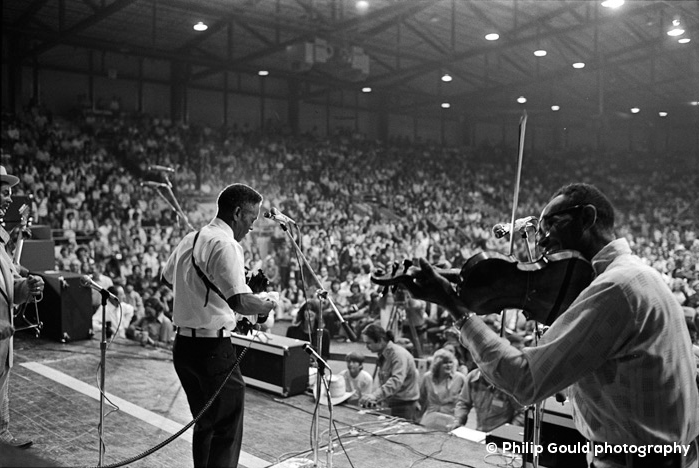

The result was A Tribute to Cajun Music on March 26, 1974, in Lafayette's Blackham Coliseum, a culturally significant event that would evolve into today's Festivals Acadiens et Creoles, a culturally rich, multi-layered festival.

"You can draw a straight line back to Lomax," said current Festivals Acadiens Director Pat Mould.

"Both that concert and the Newport concert were influenced by the Lomax recordings years before," Ancelet said.

Festivals Acadiens Beginnings

After Balfa's experience in Newport, he returned to South Louisiana to meet with James Domengeaux, chairman of the Council for Development of French in Louisiana, to discuss creating a grassroots, outreach event that celebrated Cajun and Creole culture. A gathering of 150 French journalists in Lafayette in March 1974 encouraged them to organize A Tribute to Cajun Music on March 26 in Lafayette's Blackham Coliseum.

"No one knew how the concert would be received," Ancelet said. "Honestly, when we first did this we had no idea what was going to happen, not knowing what the result would be, if anyone would come, if anyone would care."

Organizers offered the tribute in a concert setting, hoping participants would listen and appreciate the music as opposed to a dancehall-type atmosphere.

"The point was to get people to sit down and listen," Ancelet said.

"The first one was special simply not just for me but I think for everyone who attended because it was a setting in which Cajun music had never been played a concert setting," said Mould. "Up to that point we had always heard the music in the home or a dancehall. It was a momentous occasion."

"The concert was a success and struck a nerve in the community," Ancelet said, proving that a tribute to the gold mine of Cajun and Creole music of South Louisiana was much needed.

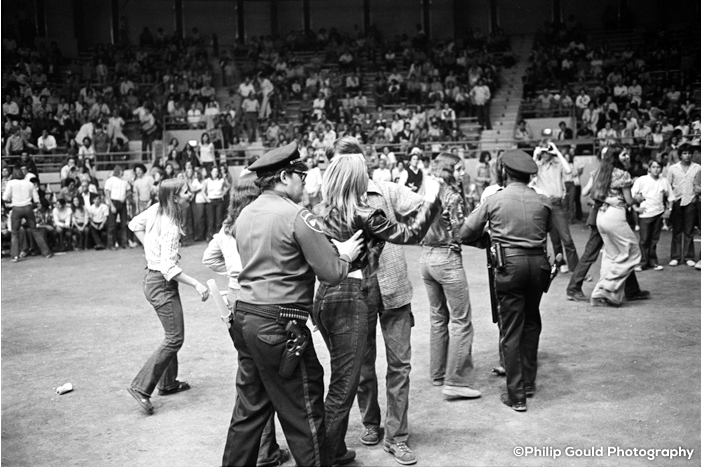

The following year, organizers presented a similar concert with the same outpouring from the public. But participants had enough of sitting on the sidelines. South Louisianans dance when music is performed; its part of their DNA. When Clifton Chenier performed his legendary zydeco music, wearing his trademark crown as Zydeco King, the crowd attempted to dance, only to be escorted by police off the floor.

"If anyone would have gotten them in an uproar it would have been Clifton Chenier," said his son, zydeco musician C.J. Chenier.

It took Clifton Chenier's pleas to the crowd to keep them in their seats.

Organizers realized that a concert-style setting wasn't going to satisfy South Louisiana crowds so by 1976 the festival moved to a fall date and to the more spacious Girard Park amphitheater in the heart of Lafayette. The Tribute to Cajun Music III allowed dancing and had now become a festival.

Over the years the initial music tribute became Festival du Musique and merged with other Lafayette festivals such as the Louisiana Native Crafts Festival (later to become the Louisiana Native and Contemporary Crafts Festival) and the Bayou Food Festival, which is why the name Festivals Acadiens et Croles remains plural.

As the years progressed, the festival continually grew. The creation of the Heritage Tent, for instance, allowed participating musicians to be interviewed. When a community board took over from the Lafayette Jaycees in 2007, three more venues were added the following year, the Dance Hall Tent, the Chef's Demo Stage (Culture Sur la Table) and a revitalized children's area (La Place des Petites). The Heritage Tent became a music stage and the Scene Atelier took its place. A Jam Tent was instituted where festivalgoers could play alongside professional musicians.

"Since then we have added the Louisiana Sports Tent, a Festival Friends Tent and amenities for the musicians as well as those who attend," explained Mould. "Better sound and staging, better signage, more food and beverage selections, along with marketing and sponsorship programs have allowed us to pay for these upgrades by attracting more people to attend and getting local businesses involved."

Festivals Acadiens Legacy

In the early years of Festivals Acadiens et Croles, most musicians were over the age of 30. Today, the festival lineup is filled with young musicians, most of whom were inspired by musicians performing at the festival, not to mention the Lomax recordings and Dewey Balfa's relentless dedication to the culture.

"The festival has always been a great draw for the younger generation and it seems like I always see more and more younger people attending and playing each year," said Grammy Award-winning musician Steve Riley.

Michael Doucet performed in bands BeauSoleil and Coteau in the early years, when musicians his age were few and far between.

"Very few people our age were playing," he said of the early years. "BeauSoleil and Coteau influenced people to play. That was good to see."

"This music being passed down from generation to generation is just a natural part of the process in our culture," said Mould. "Remember this was and still is the main way the music is taught, generationally. The festival has always made a point of putting young performers on its stages. But I have also noticed especially more so these days is our audience is getting younger, which is really cool to witness."

"We are the self celebration of all the things that make this area of the world so interesting from a cultural perspective, said Mould. "The festival is an opportunity for all of us to gather and celebrate how we live. Its an opportunity for musicians, chefs and the artists of the region to gather once a year and prove to the world that our culture is alive and well. We also allow people from outside the area to come and be a part of the experience and to bring back to wherever they came from a positive impression of the culture. And we are also doing our part to expose a younger generation to the whole process."

Ancelet, who has been involved in the festival since its inception, views Festivals Acadiens et Croles as a living organism, not a museum, morgue or culture police.

"As Dewey once said, Were not trying to preserve that thing, were trying to preserve the process that creates that thing," Ancelet explained. "We will continue to pay careful attention to see whats up. There's a lot of interesting, daring creativity going on but somehow it all remains connected, surprises us and reassures us in the same moment."

"There is no other festival anywhere that does more than Festivals Acadiens et Croles to showcase and preserve Cajun/Creole music, language and culture," said Riley. "Music, food, workshops, jam sessions, interviews, on and on. Its all there at Festivals Acadiens et Croles!"