"The Vermilion, by its union with the gulph, forms the natural communication of its inhabitants with the sea. The time is not far remote when many thousands of people will exist on the shores of this river…," William Darby, A Geographical Description of the State of Louisiana, published in 1817.

The course of the Vermilion River and what happens along its banks, like every other river in the world, have changed with the times.

For millennia throughout the prehistoric era, each time sea level made a drastic change, so would the course of what we now call the Mississippi River — and the Mississippi’s changes affected all the waters in its vicinity.

At some point between 25,000 and 125,000 years ago, the course of the Mississippi shifted to the west. In fact, for a while, the river flowed right through the Lafayette area, where it cut a new course through the coastal plains. When the course of the river shifted eastward, the mighty river left in its wake a course through the prairie — a channel for the eventual Vermilion River.

Because the Vermilion and surrounding Attakapas Country “lay at some distance from the first centers of colonization, it was not encroached upon to any great extent until late in the eighteenth century,” as recorded by John Reed Swanton in 1911.

By the 1740s, early settlers had a profitable fur and deerskin trading business along the Vermilion River. The Old Spanish Trail reached the Vermilion right about where the current Pinhook Bridge is located. The Pinhook Bridge landmark has been the epicenter of the Vermilion for centuries. Underestimating the significance of that site in terms of the history of the river and region is almost impossible.

In the midst of traders, ranchers and smugglers, the area around the Pinhook Bridge was the hub of what little commerce and activity happened along the Vermilion at the time. The small settlement was called Petit Manchac and served as a trading center for Native Americans, trappers and colonists.

During low water periods, Petit Manchac, later called Pinhook, was the farthest inland up the Vermilion River that smugglers could deliver goods up — making the Pinhook Bridge point the traditional head of navigation for the waterway. Above the Pinhook Bridge, it was called Bayou Vermilion. Below Pinhook, it was called the Vermilion River.

In 1760, Gabriel Fuselier de la Claire, originally from France, bought all the land between the Vermilion and the Bayou Teche from the Eastern Attakapas Chief Kinemo. This initial sale of land began a long string of land sales on both sides of the Vermilion.

By 1762, when France ceded Louisiana to Spain, the hardy pioneers along the Vermilion were primarily trappers, ranchers and smugglers. Some built their "stores" on barges that carried gunpowder, traps, tea and other goods to the scattered settlers, who offered furs, hides and farm products in exchange.

The Acadians began arriving in 1765. The census of 1766 listed 150 inhabitants in the Attakapas District — including 37 people in 17 households at Cöte Gelee (present day Broussard). By 1769, the population of the entire district was up to 409, according to a census taken that year by acting Gov. O’Reilly.

In the midst of the Acadians’ arrival to the Attakapas Country, smuggling along the Vermilion River was rampant. During the Spanish period, it was known as a smugglers' "highway." By the early 1800s, smuggling expanded to include the illegal slave trade.

“The bewildering rapidity with which the country was transferred from Spain to France and then to the United States cause a great deal of confusion. Neither the laws of the United States nor its language were understood,” The WPA Guide to Louisiana (2013).

Since settlers had arrived in Attakapas Country, raising cattle provided the most prosperous livelihood along the prairies of the Vermilion River. However, about 1830 most cattlemen opted to plow up their grasslands and plant cotton or sugar cane — with the intent to use the river as the primary means to transport the heavy goods. Steamboats made transporting the cotton and hogsheads of cane sugar an easier possibility than transporting by land.

As the 1850s brought rising economic prosperity to the free people of the region, tensions between the North and South were also increasing. Eventually, the great national debate of slavery and westward expansion reached a boiling point and the Civil War was launched. Because of the region’s bounty of agricultural resources, both Union and Confederate forces brought significant naval troops to the bayous throughout the Acadiana region. Early in the Civil War, the Confederate army used the region as a major foraging area.

In 1865, after the war ended, the region struggled economically. Because of extensive wartime damage along the upper Vermilion — crops were burned, livestock was killed, homes were destroyed — the region’s farmers had little to nothing to send to market. During that time and considering the problems associated with navigating the Vermilion, what cargo was ready to be sent to New Orleans likely went along the Teche.

With so much energy focused on recovery from the Civil War and the additional activity along the Vermilion, the region clambered for improvements along the Vermilion, which were slow to materialize. In 1879, Congressional legislation commissioned an engineering survey through the Army Corps of Engineers.

In June 1880, Congress appropriated $5,000 to fund the removal of navigational hazards between Abbeville and Pinhook Bridge. In February 1881, the Corps of Engineers signed a contract for $4,750 to clear “22 miles of river.” In March 1881, Congress appropriated $4,900 to underwrite the cost of closing the Vermilion’s “eastern entrance, at its mouth, by a low-water dam, and applying the balance that may remain to clearing the banks of overhanging trees, and the bed of the river of all trees, logs, and snags that may be found in it.”

Because the railroads didn’t reach New Iberia and Abbeville until later, the late-blooming steamboat traffic along the lower Vermilion thrived for years after it had virtually disappeared in other places. But the railroad eventually reached those communities too, and steamboat traffic disappeared.

By 1881, the railroad made its way from New Orleans to Houston and the region was referred to as the Attakapas Country began to grow and prosper again. The Civil War and Yellow Fever epidemic of the mid-1800s behind them, the city changed its name from Vermilionville to Lafayette in 1884.

As the ease and speed of train travel began to morph society, the Vermilion River’s place of prominence began to diminish.

In the 1930s, in response to the great flood of 1927, levees constructed around the Atchafalaya Basin cut off the flow of fresh water to the Vermilion River. This hydrological isolation led to better flood control and navigation but came at a great price to the river. The lack of fresh water led to continued pollution and pollution accumulation, leading it to gain the infamous title of “Most Polluted River in America” on national television in the 1970s.

In response to the river’s pollution, in 1984 the state of Louisiana created the Lafayette Parish Bayou Vermilion District with the primary purpose of improving the water quality and beautifying the Bayou Vermilion in Lafayette Parish in an effort to promote the bayou as a recreational and cultural asset.

After more than 40 years of work, progress is happening and the river’s water quality, oxygen levels and aquatic life are in a healthier state. Recreation on the river has also continued to increase with Bayou Vermilion District maintaining three boat launches, four canoe/kayak launches and three public parks all located along the Vermilion.

Slowly but surely the Vermilion River is returning to the tidal river it once was.

Vermilion Voyage

Experience the Vermilion River on a three-day, 50-mile, overnight paddle launching from the Acadiana Park Nature Station to Palmetto Island State Park that includes culinary, cultural…

Jesse Guidry

For most of my life I had no knowledge of the main river flowing through the city I call home. Driving over bridges throughout Lafayette and the surrounding areas, it never once crossed my mind the impact a river and its tributaries could have on a community. That is until I started working at the Bayou Vermilion District, an environmental and cultural organization that conserves and manages boat, canoe and kayak launches in addition to public parks along the Vermilion. Through my work with the Bayou Vermilion District I not only began a personal relationship with the Vermilion through paddling, but also with the concept of a watershed. Many years later I have paddled the majority of the Vermilion more times than I can count. One thing I had not done, and to my knowledge no one has done, was continuously paddle the length of the Vermilion, which runs 70 Miles throughout three parishes. But that would soon change.

After my work with the Bayou Vermilion District I settled into my role with Lafayette Travel, the local Convention & Visitors Bureau, where part of my job was to develop and curate content for the blog. Having a passion for paddling and with outdoor seeming to be an untapped market for Lafayette I decided to explore the idea of developing an overnight paddle trail along the Vermilion as a way to boost ecotourism. The concept of the blog series was simple enough, recruit an avid outdoor photographer who had never been to the South, let alone paddled a river, bayou or swamp, and capture the paddle trip that would see us on the Vermilion for 60 miles over the course of four days and three nights.

Finding the right person to anchor the series proved to be easy enough. A simple search for outdoor photographers gave me more options than I knew what to do with. Narrowing it down to three, I sent the request out and very quickly got a response from Nathaniel Martin, a native of Vancouver who develops content for Monument and always seemed to be on some adventure on his Instagram account. After some back and forth about all that was entailed he was in and all that was left was the planning. Knowing that I would need help and paddling is always more fun with a group I set out to recruit locals I knew had either a specific skill set that was needed or an existing relationship with the Vermilion. The end of planning would see a total of 10 paddlers, including myself-four photographers, one cook, two guides, Lafayette Travel’s creative director and intern as well as myself.

The culmination of everyone’s efforts results can be seen in the below series. The stories and images that follow are the experiences shared by the people on this trip captured through their words as well as images.

Nathaniel Martin

It was a cold and misty morning in Lafayette when our team rolled out of the Vermilionville parking lot. Outside the window moody clouds still hung in the sky, reminders of the downpour from the night before. We were on our way to Lake Martin, a wildlife preserve just east of the city. From Lake Martin our team would paddle 60 miles over four days, following the Bayou Vermilion all the way to the Intercoastal Waterway.

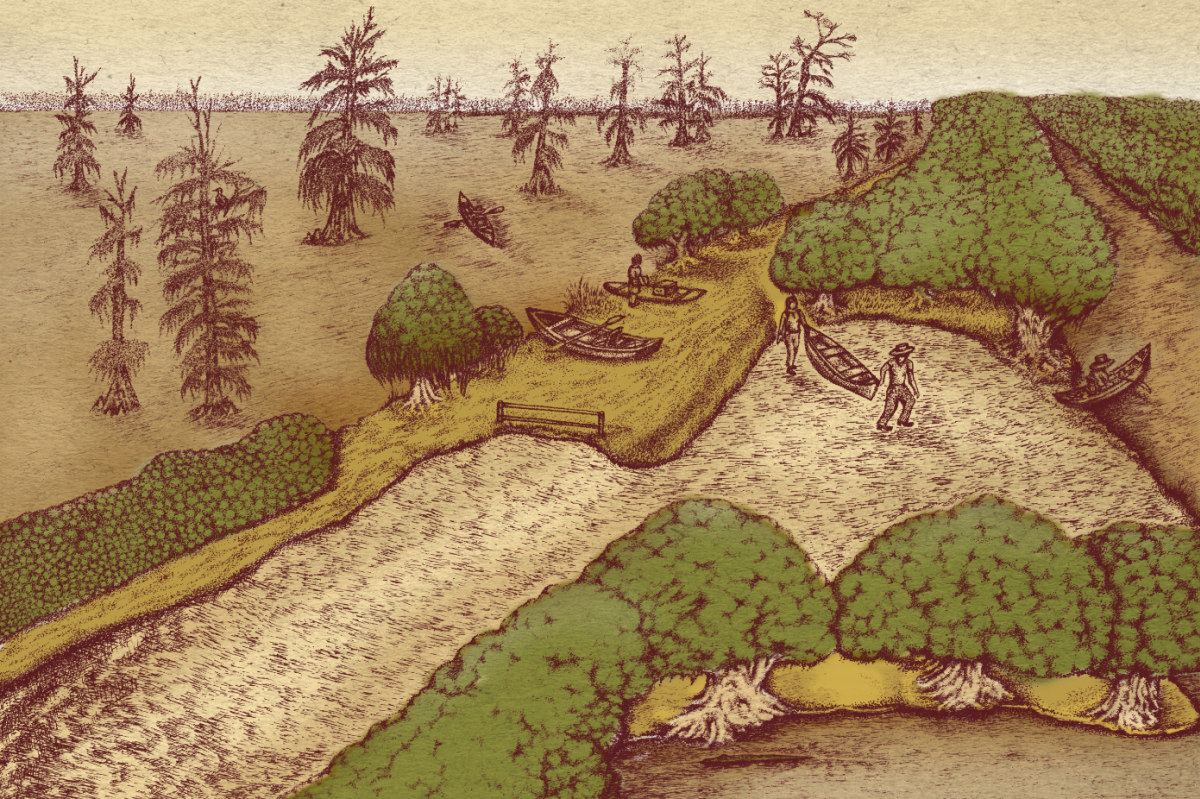

Our truck rounded a corner and we came to a stop in a muddy parking lot near the shore. We launched our vessels into the swamp. Five kayaks, three canoes, and a paddle board. Lake Martin was still and black, a perfect mirror if not for the rippling of our paddle strokes. One by one we floated through the stands of cypress trees, observing a wide array of birds lighting onto gnarled branches. Spanish moss hung lazily from the trees like curtains. The entire lake felt more like a forest in many respects. Instead of pine needles and grass this forest floor was made up of floating fields of lily pads and layers of foamy algae. It was truly unlike any place I've ever been. After about an hour of exploring we leisurely made our way back to the Evangeline Canal, and put into the Bayou Vermilion.

The Vermilion is a tidal river. Long ago high waters from the Vermilion Bay pushed their way northward until eventually intersecting with a southbound distributary. That is how the river was formed, and as a result its currents are sometimes subject to a change in direction based on rain, tides and wind. Aside from the clouds on the first morning the first three days of our trip we were met with nearly perfect conditions for paddling. Bluebird skies and gentle tailwinds allowed us to take the river at our own pace. We covered a truly diverse set of landscapes.

For the first leg of the journey took us through lush marshland. The dark green canopies of the river's banks meeting in the middle to form a tunnel of sorts. Occasionally large herons and egrets would fly out in front of us, stirred no doubt by the sound of our voices breaking up the heavy silence. As we neared Lafayette the untamed forests began to give way to rural homesteads and eventually industrial waterfronts and towering cement bridges. The river became a guide of sorts, revealing Lafayette from a different vantage. We followed it from the bustling city airport, to historic Vermilionville, to charming riverfront neighborhoods until eventually the sounds of the city subsided and we found ourselves in the wild once more.

On this trip it was those long stretches of isolation that were the most meaningful. Not isolation from people per se, because we were a group of ten, but that sense of escape that comes from leaving what is familiar and routine. With every turn of the murky brown river came some new experience. One afternoon after drawing together for lunch we decided to latch all our boats together and create a flotilla. What was once a fleet of canoes and kayaks had become one giant raft. A couple of the guys jury rigged a sail out of two oars and a tarp and we sat there, laughing in the sun, letting the wind push us further southward.

Another time I found myself alone on the river. As I paddled I could hear the unique grunting sound of egrets along the trees lining the east bank. Eventually I found a stream that seemed to be flowing from where I had placed them in the forest. I followed the water into a marsh and found myself in the middle of a nesting ground. Hundreds of white egrets and pink spoonbills lined the branches of lofty cypress trees. I watched in silence as they flew from tree to tree, feeding their young before meeting back up with team and continuing south.

Our last day on the river was by far the most challenging. From the first few paddle strokes it became apparent that there was a shift in tides on the river. Brackish water from the gulf met us head on, accompanied by strong winds. Our pace was slowed to a crawl as we struggled against the strong current. After battling our way to the Intercoastal Waterway we decided to put in at a harbor and call it a day. It was hard for me to leave having come only a few miles short of our goal, but it's just another reason to come back to Louisiana and paddle the Vermilion once more.

Leah Graeff

It seems as though the more time I spend on Lake Martin or the Vermilion River, the more I feel I’m already looking at a photograph.

They both have a way with stillness. Wind blows through cypress and tupelo trees so delicately that it’s as if the moss is fixed in its fullest expression. Herons wait patiently to glide downstream along the treetops while wood ducks blend with the shadows on the water. If I am not as still, I could miss them all.

As an artist my work focuses on relationships between the environment and the viewer, and I expected that for this trip, forming a connection to the landscape would be a priority, only I wasn’t sure how I wanted to approach it in a way I hadn’t done before.

I’ve paddled the Vermilion, and have more times than not, brought my camera along, usually leaving the images, if any, to chance. However, for these photographs, they weren’t secondary. I needed an agenda, which wasn’t anything out of the ordinary, but I was nervous that as many times before, I’d succumb to the stillness and not be able to close the shutter.

I was excited at my first experience of a collaborative photography project, which meant being on the river with four photographers, two guides, and four other project collaborators. It was a challenge, each of us on the same schedule, each looking for that “decisive moment” while being respectful of each other’s space, particularly that of our guest Nathaniel, who traveled from Canada and was experiencing the landscape for the first time.

I will admit it was a challenge to let another photographer have a shot, since it’s very difficult for a photographer to “see a photograph” and settle with not having it. When I do that, I see the image every time I close my eyes, and I say to myself, “Damn, I should have taken that shot.” However, I do tend to make things more difficult for myself, and quickly settled into playing the game of chance and control.

Over the first two days of getting used to being with a large group on the water I kept going back to the word stillness and began to search for it in my environment. I paid closer attention to moments when I was alone, when I found an object that was alone or I where I felt still or found an object I felt was very still. This also served my desire to observe. Not looking to exploit the landscape but to conserve those moments of hush.

On the third day of our trip, we paddled from The Richard Sale Barn to Palmetto Island State Park. And that’s where I found the equivalent to my own little blackberry bush (sadly, I didn’t find any actual blackberry bushes). The Vermilion wound through acres of grain silos and hidden barns. Through hundred year oaks wrapped in resurrection ferns and forgotten houses we made plans to buy. I found my piece of the river, where I wanted to be fixed, just as the moss, in my fullest expression.

Joseph Vidrine

During my time working on the Bayou Vermilion in Lafayette Parish, I regularly used my phone’s camera to document the amazing beauty of the bayou. Though the grandeur of the bayou was sometimes found in the trash problems I was tasked with alleviating, I felt it was important to record the bayou in an authentic way. Through my experience on the bayou, I formed an intimate relationship with the waterway, so when I was offered the chance to make this voyage I jumped at the opportunity.

The trip would last four days, traversing both Lafayette and Vermilion Parish, to finally reach Intracoastal City, 60 miles from our starting point. Riding on the force of a massive amount of runoff water pouring out of Lafayette’s urban core, myself and ten other paddlers/photographers embarked on the trip of a lifetime. As we launched our boats on a calm, foggy morning, there was an excitement amongst the group of what was to come.

The Bayou Vermilion is the natural feature that has shaped the physical and cultural environment that is Acadiana. What was once a thriving economic highway for the area has over the years lost its luster in the hearts and minds of most who live in proximity. The bayou is viewed by many as a polluted ditch of sorts-- ridden with dead cows and discarded washing machines. What people may not know is efforts to clean and improve the condition and perception of the waterway have been carried out for years. The Bayou Vermilion District’s bayou operations division is tasked with daily trash abatement practices, water quality testing, and the clearing of navigational obstacles within Lafayette Parish. Though the BVD’s presence in the natural system is beneficial, the organization alone cannot eradicate the trash problem without the help of citizens of Lafayette and surrounding parishes. It is necessary for all to properly store and dispose of waste as well as prevent it from escaping into the natural environment.

My interest in the bayou has always been the interaction of humans with the surrounding environments. How is it that someone can cross over Pinhook bridge every day for work, but overlook the natural beauty that flows beneath? When did we become so disconnected from our waterway and is this a problem unique to the urban setting? Does it reach the more rural locations along the bayou as well?

The voyage south was the furthest I’ve had the opportunity to paddle on the Bayou Vermilion. Observing from a paddle craft offered a unique perspective that allowed me to capture the bayou from water level. It is exciting to recognize familiar Lafayette river-front residential properties and float underneath landmark bridges with cars buzzing overhead. Southside Park, just past Eloi Broussard road in Lafayette, would be where we would set up camp for the first night, followed by the Richard Sale Barn and Palmetto Island State Park for the second and third nights.

As the current took me further south past the parish boundary, the bayou started to widen and slow down. Even on an early spring day, young jet skiers enjoyed a ride on the bayou, while family party barge excursions passed by in opposite directions. Oil and fishing industry became more evident as we paddled on, fleets of shrimp trollers, pogey boats and jack up oil rigs lined the banks of the water way. Cypress groves and bottomland hardwood forests soon became distant scenes. Roso cane and spartina marsh grasses started to appear. I started to feel a familiar gulf breeze and the water became more salty. The pull-out point, Maxie Pierce boat landing in Intracoastal City, marked the end of our float and the entry back into the reality that is Lafayette rush hour traffic.

On the last morning of the trip, I took the opportunity to do some paddling on my own and went ahead of the group. An hour or so into my paddle I rounded a meander in the bayou just south of Palmetto Island State Park-- a bald eagle flying overhead caught my attention. As I floated closer, there was its pair perched in a tree on the west bank. My boat drifted toward it and the massive eagle wearily stared at me then swooped down from its resting place and flew away. The eagle is a symbol of many strong things. For me in that instance, it represented the natural beauty that can be found almost anywhere in the world-- the beauty that is found in our backyards. My hope is that the photos and words of this project influence someone to take advantage of the natural beauty that encompasses our beautiful state and I challenge future generations to explore, fish and care for the Mighty Bayou Vermilion.

Kristie Cornell

As a geologist, naturalist, and traveler, I have always found myself interested in the intersection of landscape and culture. Rivers and streams sculpt the Earth’s surface and serve as important focal points for settlement. I was excited to join this crew to see for myself, as well as through the eyes of others, how the Bayou Vermilion shapes the region I call home.

Unfortunately, I wouldn’t be able to make the whole trip to Intracoastal Waterway because of work commitments, so I would have to make do with only two days and just over thirty miles of paddling.

We met at Vermilionville to load up our gear and transport everything to nearby Lake Martin, where our trip would begin. I knew and had paddled with many of the people involved, and was looking forward to more time on the water with them. Lake Martin at daybreak is one of my favorite places to kayak, and this morning was no exception. Our boats cut through the thick fog and still water as the silence gave way to the chattering of awakening birds. We were fortunate to catch glimpses of great egrets, great blue herons, anhinga, a great horned owl, and a bald eagle perched amongst the cypress and tupelo.

Portaging across the levee at the northern end of the lake, we continued westward towards the Bayou Vermilion along the Evangeline Canal. The canal cuts through a large wetland area, and leaning trees and overhanging branches arch across the waterway, making a long, straight tunnel to the bayou. The bright green of their new growth reflected in the smooth surface of the silty water, and large patches of spiderwort were blooming along the banks.

Meeting the Vermilion, we paddled on through the wetlands and into increasing development as we approached Lafayette. Rounding a bend in the river along the runway of the Lafayette Regional Airport, we made our first stop at Vermilionville for lunch at their restaurant, La Cuisine de Maman. After a quick walk through the grounds of Vermilionville, we were back on the water and traveling through Lafayette proper.

Seeing a city from the water is to view it from a much different perspective than what we are used to. Backyards are centered on enjoying the view, and we saw lots of people taking advantage of patios and decks, having coffee and waving as we passed. I often found myself losing a sense of where we were geographically, my mind so accustomed to the network of roadways through town and less familiar with the route of the bayou. My sense of direction would reorient itself occasionally when we passed landmarks of familiar neighborhoods or bridges.

Seeing a city from the water is to view it from a much different perspective than what we are used to. Backyards are centered on enjoying the view, and we saw lots of people taking advantage of patios and decks, having coffee and waving as we passed. I often found myself losing a sense of where we were geographically, my mind so accustomed to the network of roadways through town and less familiar with the route of the bayou. My sense of direction would reorient itself occasionally when we passed landmarks of familiar neighborhoods or bridges.

The end of our first day came after over sixteen miles of paddling. Thanks to the generosity of the Bayou Vermilion District, we were allowed to set up camp for the night at Southside Park, a public park with a beautiful pavilion overlooking the bayou, and a canoe/kayak launch and dock that gives convenient access to boaters.

The second day of the trip was an additional sixteen miles from south Lafayette to Abbeville. This section of the river brought us out of the city, south through the town of Milton, and into more rural stretches of Vermilion Parish. This was a less wild, but beautiful section of the river, and we spotted quite a bit of wildlife, from red-eared sliders to hawks, and even a swallow-tailed kite.

We pulled the boats out of the water at the Richard Sale Barn in Abbeville, and while the rest of the crew set up their camp for the night, I was able to wander around the old barns, and see the beautiful auction house turned music venue. In addition to being able to see my home from a different vantage point than I’m used to, this trip was also fun because of a personal connection to the river. My aunt and uncle live in the house my grandparents built on the Vermilion, and I was able to stop to visit my aunt for a minute when we passed their house. My dad also lives on the river, farther downstream in Milton. He also came out to wave as we went by. But what really made the trip memorable was the group of people that came together for this adventure. From kayaks, canoes, paddleboards and rafts, we paddled, floated, and sailed down the bayou and had a blast along the way.